Recognizing the Interconnections

between Population, Environment, Economic, and Development Issues and Solutions

Abstract:

The economic, environmental, population and political problems the world today faces have their core causes intertwined as much as their potential solutions. Attention to one causes corresponding influences on the others both positive and negative; but all must be solved simultaneously so that a new balance can be found in a circular system uniting divisions previously created by linear forces. The “take-make-waste” model is archaic and toxic. Through careful analysis of world systems and a systematic restructuring of those elements to achieve a balance, “we can build a global community where the basic needs of all people are satisfied – a world that will allow us to think of ourselves as civilized.” (Brown, p.265, 2009).

INTRODUCTION

The news stories are constant; drought, hunger, earthquakes, poverty – and they are becoming more frequent. As the population surges forward, squeezing the capacity of the planet by sheer demand for resources necessary to solve developmental and integration issues, the economy is stretched and the environment desecrated. Hinrichsen and Bryant detail: “Most developed economies currently consume resources much faster than they can regenerate. Most developing countries with rapid population growth face the urgent need to improve living standards. As we humans exploit nature to meet present needs, are we destroying resources needed for the future?” (2000). More specifically, are we not simply destroying future resources, but the critical necessary resources for solving the problems at all?

Indeed, “how people preserve or abuse the environment could largely determine whether living standards improve or deteriorate (emphasis added). Growing human numbers, urban expansion, and resource exploitation do not bode well for the future. Without practicing sustainable development, humanity faces a deteriorating environment and may even invite ecological disaster.” (Hinrichsen et. al, 2000). So do policy makers put pressure on fixing the economy, the environment, curbing population growth, or pursuing integration and education? The answer is fixing everything at the same time, because no one problem can be addressed without affecting the others. No lasting changes can be made without a comprehensive approach.

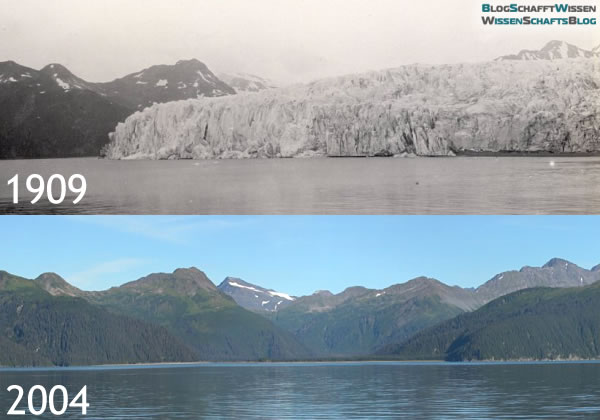

Ocean Garbage Patch

Further examination of the interrelations between the environment, economy, and population can be understood with an example involving water access and global warming. For instance, “if all the earth’s mountain glaciers melted, they would raise sea level only a matter of inches. But it is the summer ice melt from these glaciers that sustains so many of the world’s rivers during the dry season.” (Brown, p. 66, 2009). Here is an example of that interrelation; the day-to-day water shortages of people living near rivers supplied with glacier melt water can be practically combated with technology, industry, or commoditizing water. But that is only temporary; the problems will continue – to get worse – until the root cause is identified and eliminated – global warming. At some point, the practicality of “buying” a solution is obsolete.

In another example, the clear-cutting of forests is practiced to increase arable land, clear room for industry, and supply materials for production. But clear-cut areas, “in contrast to forests, which act like giant sponges that hold water in their leaves…clear-cut areas don’t hold soil and don’t absorb water. During heavy rains, water just runs off clear-cut hills, causing mudslides, flooding, and erosion.” (Leonard, p.7, 2010). The cycle of degradation is thus self-reinforcing, and societies that cut corners (all of them) to save a dollar, or a tree, or a person, end up paying for it elsewhere.

Clear-Cutting

Efforts to combat hunger, improve housing, supply water, and contain diseases or disasters are critical and not to be diminished in importance. Due to the inherent urgency of, for example, a food crisis, there is more adequate attention to detail. Leonard summarizes: “While the challenges are interconnected and system-wide, the responses are often partial, focused on just one area – like improving technologies, restricting population growth, or curbing the consumption of resources.” (p. xxi, 2010). However, these issues – population, development, etc. are symptoms of other bigger (in physiology, not significance), slow-growing problems like environmental destruction.

Water distribution relief efforts

Environmental problems are controversial, misconstrued, and readily fly under the radar due to their long-term nature; if a person loses their job and cannot afford to feed their family, that problem is more immediate than coastal flooding increasing over a 20-year period. But, is it more important? Instead, the interrelated nature of the problems mandates no measure of importance being weighed, but simply responding to each issue in tandem. Significantly, given their dichotomous disciplines, “environmentalists and economists increasingly agree that efforts to protect the environment and to achieve better living standards can be closely linked and are mutually reinforcing.” (Hinrichsen et. al, 2000). But environmentalists and economists can and have worked together successfully, as is the case in Iceland, where the “use of geothermal energy to heat almost ninety percent of its homes has largely eliminated coal for this use.” (Brown, p.127, 2009). This is a model the rest of the world would do well to emulate.

Iceland Clean Geothermal Plant & hot spring

Finding a method to slow “the increase in population, especially in the face of rising per capita demand for natural resources, can take pressure off the environment and buy time to improve living standards on a sustainable basis” (Hinrichsen et. al, 2000). More progress must be made in liberating women, expanding reproductive resources, and ensuring adequate medical care, while also alleviating economic problems in order to decrease population growth. People in developing countries cannot be expected to or relied upon to stop the cross-discipline crisis; they lack the education, the resources, or the motivation. Therefore, “North-South cooperation is vital to success in ending absolute poverty, a further element in the ongoing environmental dilemma. For those eking out a living, environmentally sound practices are a luxury, not a choice.” (UNFPA, 1999). As citizens of developed countries, we have consumer power to choose which policies we want continued, whether or not we are aware of it.

Leonard breaks the issues surrounding global cooperation efforts down further: “the structure of the global economy, a group of global regulatory institutions, and a set of agreements that have been worked out between countries to promote trade and ‘growth’. Uncovering the pervasive role of trade agreements and international financial institutions is crucial…they establish the rules by which not only the global distribution system, but the whole of the take-make-waste economic model operates.” (p. 127, 2010). For example, 18% of the funding for the World Bank is derived from U.S. sources, meaning that U.S. citizens are paying into and financially supporting World Bank policies and programs. Additionally, the majority required for decisions within the World Bank is 85%, meaning that the U.S. has veto power over any decisions. Leonard illuminates: “This means the United States has a disproportionate share of influence over both the IMF and World Bank. And it means we U.S. citizens are involved by providing our tax dollars, as well as by benefiting from interest repayments the World Bank makes on its bonds that are bought by our pension funds, municipalities, and church or university endowments. We’re paying for all these environmentally destructive projects, ruthless economic reforms, and bad loans that are suffocating many developing countries’ economies. So we have both the responsibility and the right to check out what the IMF and World Bank are doing, and to rein them in.” (p. 131, 2010).

IMF

The challenge of “saving the world” falls squarely upon the shoulders of the developed countries. Truly, where it belongs, considering it was through their development that the world was diminished. But finding blame or intent of malice within the disproportionate prosperity is as barren in possibility as the once-fertile copses of Mangrove trees in El Salvador. The many moieties of each problem must be connected with each other, so that every solution proposed can be analyzed from all angles, without exclusion of details. Brown explains: “mobilizing to save civilization means fundamentally restructuring the global economy in order to stabilize climate, eradicate poverty, stabilize population, restore the economy’s natural support systems, and, above all, restore hope. We have the technologies, economic instruments, and financial resources to do this. The United States, the wealthiest society that has ever existed, has the resources to lead this effort.” (p.261, 2009).

It is also the United States that uses a disproportionate share of the world’s resources, although everyone in developed countries are guilty: “around the world, current consumption patterns are destroying remaining environmental resources and the services that the earth provides and exacerbating inequalities. The crises of poverty, inequality, and the environment are all related – and they are all related to consumption.” (Leonard, p.181, 2010). Does that mean we as consumers can then shop our way out of collapse? Could simply buying all organic foods, bringing our own shopping bags, and avoiding Wal-Mart save society? Brown explains: “People often expect me to talk about lifestyle changes, recycling newspapers, or changing light bulbs. These are essential, but they are not nearly enough. We now need to restructure the global economy, and quickly. It means becoming politically active, working for the needed changes. Saving civilization is not a spectator sport.” (p. 266, 2009). So it is more than changing our day-to-day habits, it is changing the way we perceive everything in the world.

Instead of buying the newest cell phone, with GPS, HD, and 4G, created with the idea of “planned obsolescence” pioneered in 1932 by Bernard London in his book “Ending the Depression through Planned Obsolescence”, we can stop. We can think. Do we really need to “keep our factories humming along”? Are the problems that initiated this Depression-era practice still relevant – and if they are – then does it even work to correct them? No, the problems are still here, and they are not getting better. Buying into the identity and status-comforts that snuggle up with advertising is folly. In his book, The Bridge to the End of the World, Gus Speth explains: “Psychologists see people as hardwired to find security by both ‘sticking out’ and ‘fitting in’. Consumption serves both goals; the culture of capitalism and commercialism emphasizes both sticking out and fitting in through possessions and their display.” But psychologists will also tell you that people are their own worst enemies on this matter, for although we are hardwired to be consumers, “the single biggest contribution to our happiness is the quality of our social relationships.” (Leonard, p.175, 2010).

The continuing plummet into ruin is not because of lack of effort, in every field people are working towards solutions to their specific problems. Our mutually assured destruction is complete only if we continue to not work together: across race, class, ethnicity, sex, gender, orientation, ideology, geographic location, and religion (or non-religion). Loeb articulates this new way of being: “It must become a lifelong process, one that links our lives to the lives of others, our souls to the souls of others, in a chain of being that reaches both backward and forward, connecting us with all that makes us human.” (p. 349, 1999). Only through bringing our doubts to light can we dispel the shadows that cling desperately to the fear of change. In the words of Rabbi Hillel, “If I am not for myself, who will be for me? And if I am only for myself, what am I?” Embracing others, breathing empathy and compassion through service, work, and change in the system is the only solution. And, Hillel correctly asks once agin, “If not now, when?”

next Netflix series, we must rise to the occasion, finding strengths unforeseen. We must think

long-term with intentional planning, and reinvent ourselves and our lives. Brown makes it

brutally clear: “The choice will be made by our generation, but it will affect life on Earth for all

generations to come.” (p.268, 2009).

References

Brown, Lester R. 2009. Plan B 4.0. Earth Policy Institute. W.W. Norton & Company: New York.

Maquet, Albert. 1958. Albert Camus : The Invincible Summer. p. 86.

Hinrichsen, Don; Robey, Bryant. October 2000. Population and the Environment: The Global Challenge. Action Bioscience. Retrieved from: http://www.actionbioscience.org/environment/hinrichsen_robey.html

Leonard, Annie. 2010. The Story of Stuff. Free Press: New York.

Loeb, Paul Rogat. 1999. Soul of a Citizen. St. Martin’s Griffin: New York.

UNFPA. 1999. Population and Sustainable Development. Retrieved from:

http://www.unfpa.org/6billion/populationissues/development.htm

No comments:

Post a Comment